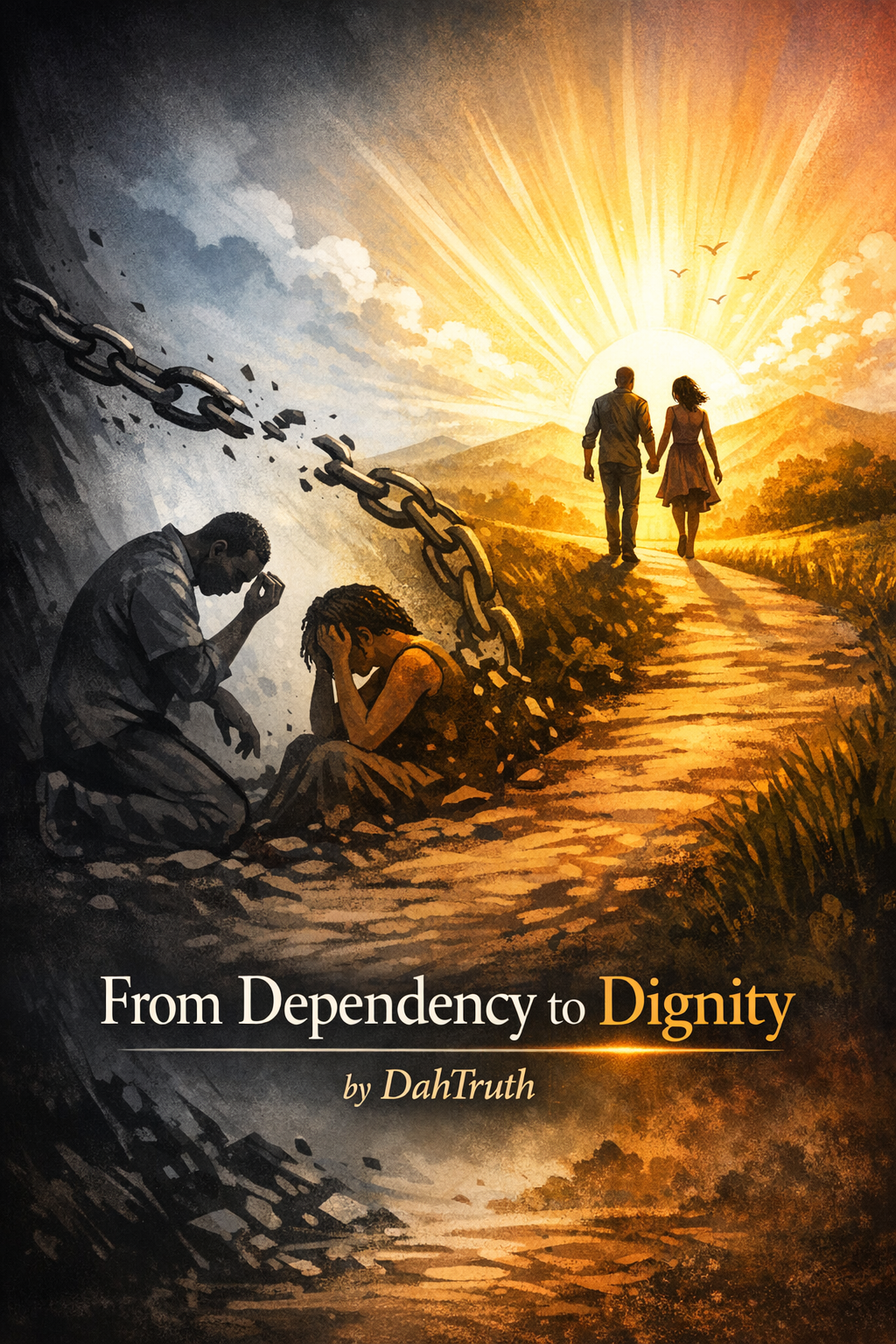

From Dependency to Dignity

“No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.”

— Booker T. Washington

To be successful meant getting a job and having enough to live on. I knew there was something called the American Dream, but in my family it was defined much more narrowly. Success was not stardom, fame, wealth, or travel. It was stability. It was survival. Our world was small, and very few people we knew had access to anything beyond that.

Some families had cars. We lived in an apartment, and the rent was paid by the government. Once a month, food came in through food stamps. School clothes arrived in September, a couple of outfits in December, maybe one during the summer for the Fourth of July. And Easter. We always had an Easter outfit. My mother sent us to church, though she never went herself.

There were good times too. We went to my grandmother’s house to play with our cousins. Those were good days. She had an apple tree in her yard and a grapevine along the fence. We ate apples that had fallen to the ground and sweet grapes straight off the vine. She kept a garden where she grew collard greens and tomatoes. It was a simple life, but it was full in ways I did not understand then. It is very different from the life I live today.

We went to school with a single expectation, to graduate and get a job. College was not part of the plan for my family. It was something other families talked about. Not mine.

I graduated from high school in 1986 and remember thinking, now what. Life answered quickly. I got a job. Then a car. Then an apartment. I had a son. Then, before I knew it, I had two sons. I married, owned a home, graduated from college, divorced, and married again. Life kept moving.

All the while, I worked. I maintained jobs. I stayed busy building a life. I did not have the time or the luxury to sit still and think about racism, discrimination, or oppression. Survival required focus. Reflection required time.

It is only now, as I am growing older, that I have had the space to look back. This week, that reflection was prompted by reading Donald Trump’s national security strategy.

“Education must not simply teach work. It must teach life.”

What struck me was not the document’s overall posture toward the world, but one specific section focused on Africa. The strategy called for shifting away from heavy investment in USAID and toward economic engagement through trade and strategic partnerships. The reasoning was straightforward. When nations rely too heavily on aid, they lose the incentive and ability to develop their own capabilities.

That idea stayed with me.

It made me think about American Descendants of Slavery and the similar dilemma facing our community. Since the 1960s, we have increasingly relied on social systems to survive. Public housing. Medicaid. Welfare programs. Food stamps. These systems did not exist in the same way prior to the Civil Rights era, yet our communities endured.

I am not arguing that these systems are unnecessary today. Many of them provide stability and relief. But aid should not replace agency. We have failed to think strategically about how these systems are used and whether they strengthen or weaken long-term independence.

At some point, reliance must give way to capability. Dependency must give way to development.

We are an extraordinarily resilient and talented people. We have survived obstacles that would have destroyed other groups. We continue to exist. We continue to adapt. Yet too often, we wait for opportunity to be created by political parties, corporations, or institutions that do not truly represent us.

This dependence is reinforced not only by politicians, but by a media ecosystem that profits from keeping us locked into narratives of grievance. Figures like Roland Martin insist that we cannot survive without permanent reliance on social systems. Don Lemon speaks endlessly about white racism while living far removed from the communities he claims to represent. Joy Reid, a first-generation immigrant, regularly uses the suffering of American Descendants of Slavery as political currency while advancing causes that do not address our decline.

Podcasts and platforms such as Native Land Podcasts urge us to emotionally invest in every global struggle, every identity movement, and every grievance except our own. We are told to carry the weight of everyone else’s injustice while our citizenship, our families, and our future remain unresolved.

This constant reinforcement of victimhood is not accidental. It keeps us dependent. It keeps us distracted. It keeps us from demanding outcomes.

This helps explain why American Descendants of Slavery lack meaningful representation within the Democratic Party. Our suffering is discussed endlessly, but real solutions are rarely delivered. Figures such as Maxine Waters, Jasmine Crockett, and Cory Booker speak passionately about systemic racism while offering little in the way of substantive legislation focused on housing ownership, prison reform, education reform, or economic independence.

Instead, attention is diverted elsewhere. One cause replaces another. Banking crises give way to healthcare debates. Healthcare debates give way to foreign wars. Immigration debates dominate the discourse. Once again, healthcare returns to the forefront, framed primarily through race, as if policy failure can be reduced to skin color rather than outcomes.

Democratic leadership has become performative rather than productive. Outrage is amplified. Legislation stalls. This pattern has persisted for decades.

I have come to believe that separation from the Democratic Party is necessary. But separation alone is not enough. The question remains, where do we go next.

Any alternative must be grounded in citizenship, responsibility, and agency. It cannot be built on grievance politics or racial symbolism alone. It must recognize American Descendants of Slavery as a distinct community with specific challenges and commit to real solutions rather than recycled narratives.

That also requires rejecting ideologies that actively undermine our families. The insistence that biological reality is irrelevant, or that abortion represents empowerment while our population declines, does not strengthen our future. These ideas weaken it.

As I reflect on all of this, I am struck by how little has changed since the debates between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Education and work both matter. Education must be reformed so that it strengthens critical thinking and identity rather than imposing ideological conformity. Work must be honored as skill, craftsmanship, and stewardship.

We must reclaim the dignity of using both the mind and the hands. Farming. Trades. Technical skill. Innovation rooted in practicality. When I see Black farmers or Black horsemen in Texas, I am reminded that this was once us. Builders. Producers. Stewards.

Stories like the one told in Horse by Geraldine Brooks remind us that our contributions were foundational and enduring. An enslaved Black man helped shape a champion racehorse whose lineage still exists today. These stories are real. They are ours. And they deserve to be centered.

Instead, our narrative is diluted. Overshadowed by causes that do not address our survival or our future. Our children are confused. Our communities are fractured. Our identity is treated as interchangeable.

We need a different approach. One grounded in faith, responsibility, skill, and self-determination. One that builds rather than performs outrage.

The question I continue to wrestle with is not whether change is needed, but how it begins. Who leads it. How it is structured. How we move from separation to construction.

Walking away is not enough. We must build something better in its place.

That is the work ahead.